Ensemble learning

In statistics and machine learning, ensemble methods use multiple models to obtain better predictive performance than could be obtained from any of the constituent models.[1][2][3] Unlike a statistical ensemble in statistical mechanics, which is usually infinite, a machine learning ensemble refers only to a concrete finite set of alternative models.

Contents |

Overview

Supervised learning algorithms are commonly described as performing the task of searching through a hypothesis space to find a suitable hypothesis that will make good predictions with a particular problem. Even if the hypothesis space contains hypotheses that are very well-suited for a particular problem, it may be very difficult to find a good one. Ensembles combine multiple hypotheses to form a (hopefully) better hypothesis. In other words, an ensemble is a technique for combining many weak learners in an attempt to produce a strong learner. The term ensemble is usually reserved for methods that generate multiple hypotheses using the same base learner. The broader term of multiple classifier systems also covers hybridization of hypotheses that are not induced by the same base learner.

Evaluating the prediction of an ensemble typically requires more computation than evaluating the prediction of a single model, so ensembles may be thought of as a way to compensate for poor learning algorithms by performing a lot of extra computation. Fast algorithms such as decision trees are commonly used with ensembles (for example Random Forest'), although slower algorithms can benefit from ensemble techniques as well.

Ensemble theory

An ensemble is itself a supervised learning algorithm, because it can be trained and then used to make predictions. The trained ensemble, therefore, represents a single hypothesis. This hypothesis, however, is not necessarily contained within the hypothesis space of the models from which it is built. Thus, ensembles can be shown to have more flexibility in the functions they can represent. This flexibility can, in theory, enable them to over-fit the training data more than a single model would, but in practice, some ensemble techniques (especially bagging) tend to reduce problems related to over-fitting of the training data.

Empirically, ensembles tend to yield better results when there is a significant diversity among the models[4] [5]. Many ensemble methods, therefore, seek to promote diversity among the models they combine[6][7]. Although perhaps non-intuitive, more random algorithms (like random decision trees) can be used to produce a stronger ensemble than very deliberate algorithms (like entropy-reducing decision trees)[8]. Using a variety of strong learning algorithms, however, has been shown to be more effective than using techniques that attempt to dumb-down the models in order to promote diversity.[9]

Common types of ensembles

Bayes optimal classifier

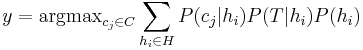

The Bayes Optimal Classifier is an optimal classification technique. It is an ensemble of all the hypotheses in the hypothesis space. On average, no other ensemble can outperform it, so it is the ideal ensemble[10]. Each hypothesis is given a vote proportional to the likelihood that the training dataset would be sampled from a system if that hypothesis were true. To facilitate training data of finite size, the vote of each hypothesis is also multiplied by the prior probability of that hypothesis. The Bayes Optimal Classifier can be expressed with following equation:

where  is the predicted class,

is the predicted class,  is the set of all possible classes,

is the set of all possible classes,  is the hypothesis space,

is the hypothesis space,  refers to a probability, and

refers to a probability, and  is the training data. As an ensemble, the Bayes Optimal Classifier represents a hypothesis that is not necessarily in

is the training data. As an ensemble, the Bayes Optimal Classifier represents a hypothesis that is not necessarily in  . The hypothesis represented by the Bayes Optimal Classifier, however, is the optimal hypothesis in ensemble space (the space of all possible ensembles consisting only of hypotheses in

. The hypothesis represented by the Bayes Optimal Classifier, however, is the optimal hypothesis in ensemble space (the space of all possible ensembles consisting only of hypotheses in  ).

).

Unfortunately, Bayes Optimal Classifier cannot be practically implemented for any but the most simple of problems. There are several reasons why the Bayes Optimal Classifier cannot be practically implemented:

- Most interesting hypothesis spaces are too large to iterate over, as required by the

.

. - Many hypotheses yield only a predicted class, rather than a probability for each class as required by the term

.

. - Computing an unbiased estimate of the probability of the training set given a hypothesis (

) is non-trivial.

) is non-trivial. - Estimating the prior probability for each hypothesis (

) is rarely feasible.

) is rarely feasible.

Bootstrap aggregating (bagging)

Bootstrap aggregating, often abbreviated as bagging, involves having each model in the ensemble vote with equal weight. In order to promote model variance, bagging trains each model in the ensemble using a randomly-drawn subset of the training set. As an example, the random forest algorithm combines random decision trees with bagging to achieve very high classification accuracy[11].

Boosting

Boosting involves incrementally building an ensemble by training each new model instance to emphasize the training instances that previous models mis-classified. In some cases, boosting has been shown to yield better accuracy than bagging, but it also tends to be more likely to over-fit the training data. By far, the most common implementation of Boosting is Adaboost, although some newer algorithms are reported to achieve better results .

Bayesian model averaging

Bayesian model averaging is an ensemble technique that seeks to approximate the Bayes Optimal Classifier by sampling hypotheses from the hypothesis space, and combining them using Bayes' law.[12] Unlike the Bayes optimal classifier, Bayesian model averaging can be practically implemented. Hypotheses are typically sampled using a Monte Carlo sampling technique such as MCMC. For example, Gibbs sampling may be used to draw hypotheses that are representative of the distribution  . It has been shown that under certain circumstances, when hypotheses are drawn in this manner and averaged according to Bayes' law, this technique has an expected error that is bounded to be at most twice the expected error of the Bayes optimal classifier [13]. Despite the theoretical correctness of this technique, however, it has a tendency to promote over-fitting, and does not perform as well empirically as simpler ensemble techniques such as bagging[14].

. It has been shown that under certain circumstances, when hypotheses are drawn in this manner and averaged according to Bayes' law, this technique has an expected error that is bounded to be at most twice the expected error of the Bayes optimal classifier [13]. Despite the theoretical correctness of this technique, however, it has a tendency to promote over-fitting, and does not perform as well empirically as simpler ensemble techniques such as bagging[14].

Pseudo-code

function train_bayesian_model_averaging(T) z = -infinity For each model, m, in the ensemble: Train m, typically using a random subset of the training data, T. Let prior[m] be the prior probability that m is the generating hypothesis. Typically, uniform priors are used, so prior[m] = 1. Let x be the predictive accuracy (from 0 to 1) of m for predicting the labels in T. Use x to estimate log_likelihood[m]. Often, this is computed as log_likelihood[m] = |T| * (x * log(x) + (1 - x) * log(1 - x)), where |T| is the number of training patterns in T. z = max(z, log_likelihood[m]) For each model, m, in the ensemble: weight[m] = prior[m] * exp(log_likelihood[m] - z) Normalize all the model weights to sum to 1.

Bayesian model combination

Bayesian model combination (BMC) is an algorithmic correction to BMA. Instead of sampling each model in the ensemble individually, it samples from the space of possible ensembles (with model weightings drawn randomly from a Dirichlet distribution having uniform parameters). This modification overcomes the tendency of BMA to converge toward giving all of the weight to a single model. Although BMC is somewhat more computationally expensive than BMA, it tends to yield dramatically better results. The results from BMC have been shown to be better on average (with statistical significance) than BMA, and bagging[15].

The use of Bayes' law to compute model weights necessitates computing the probability of the data given each model. Typically, none of the models in the ensemble are exactly the distribution from which the training data was generated, so all of them correctly receive a value close to zero for this term. This would work well if the ensemble were big enough to sample the entire model-space, but such is rarely possible. Consequently, each pattern in the training data will cause the ensemble weight to shift toward the model in the ensemble that is closest to the distribution of the training data. It essentially reduces to an unnecessarily complex method for doing performing selection.

The possible weightings for an ensemble can be visualized as lying on a simplex. At each vertex of the simplex, all of the weight is given to a single model in the ensemble. BMA converges toward the vertex that is closest to the distribution of the training data. By contrast, BMC converges toward the point where this distribution projects onto the simplex. In other words, instead of selecting the one model that is closest to the generating distribution, it seeks the combination of models that is closest to the generating distribution.

The results from BMA can often be approximated by using cross-validation to select the best model from a bucket of models. Likewise, the results from BMC may be approximated by using cross-validation to select the best ensemble combination from a random sampling of possible weightings.

Pseudo-code

function train_bayesian_model_combination(T)

For each model, m, in the ensemble:

weight[m] = 0

sum_weight = 0

z = -infinity

Let n be some number of weightings to sample.

(100 might be a reasonable value. Smaller is faster.

Bigger leads to more precise results.)

for i from 0 to n - 1:

For each model, m, in the ensemble: // draw from a uniform Dirichlet distribution

v[m] = -log(random_uniform(0,1))

Normalize v to sum to 1

Let x be the predictive accuracy (from 0 to 1) of the entire ensemble, weighted

according to v, for predicting the labels in T.

Use x to estimate log_likelihood[i]. Often, this is computed as

log_likelihood[i] = |T| * (x * log(x) + (1 - x) * log(1 - x)),

where |T| is the number of training patterns in T.

If log_likelihood[i] > z: // z is used to maintain numerical stability

For each model, m, in the ensemble:

weight[m] = weight[m] * exp(z - log_likelihood[i])

z = log_likelihood[i]

w = exp(log_likelihood[i] - z)

For each model, m, in the ensemble:

weight[m] = weight[m] * sum_weight / (sum_weight + w) + w * v[m]

sum_weight = sum_weight + w

Normalize the model weights to sum to 1.

Bucket of models

A "bucket of models" is an ensemble in which a model selection algorithm is used to choose the best model for each problem. When tested with only one problem, a bucket of models can produce no better results than the best model in the set, but when evaluated across many problems, it will typically produce much better results, on average, than any model in the set.

The most common approach used for model-selection is cross-validation selection. It is described with the following pseudo-code:

For each model m in the bucket:

Do c times: (where 'c' is some constant)

Randomly divide the training dataset into two datasets: A, and B.

Train m with A

Test m with B

Select the model that obtains the highest average score

Cross-Validation Selection can be summed up as: "try them all with the training set, and pick the one that works best"[16].

Gating is a generalization of Cross-Validation Selection. It involves training another learning model to decide which of the models in the bucket is best-suited to solve the problem. Often, a perceptron is used for the gating model. It can be used to pick the "best" model, or it can be used to give a linear weight to the predictions from each model in the bucket.

When a bucket of models is used with a large set of problems, it may be desirable to avoid training some of the models that take a long time to train. Landmark learning is a meta-learning approach that seeks to solve this problem. It involves training only the fast (but imprecise) algorithms in the bucket, and then using the performance of these algorithms to help determine which slow (but accurate) algorithm is most likely to do best.[17]

Stacking

The crucial prior belief underlying the scientific method is that one can judge among a set of models by comparing them on data that was not used to create any of them. This same prior belief underlies the use in machine learning of bake-off contests to judge which of a set of competitor learning algorithms is actually best.

This prior belief can also be used by a single practitioner, to choose among a set of models based on a single data set. This is done by partitioning the data set into a held-in data set and a held-out data set; training the models on the held-in data; and then choosing whichever of those trained models performs best on the held-out data. This is the cross-validation technique, mentioned above.

Stacking (sometimes called stacked generalization) exploits this prior belief further. It does this by using performance on the held-out data to combine the models rather than choose among them, thereby typically getting performance better than any single one of the trained models.[18]. It has been successfully used on both supervised learning tasks (regression)[19] and unsupervised learning (density estimation)[20]. It has also been used to estimate Bagging's error rate[21][3].

Because the prior belief concerning held-out data is so powerful, stacking often out-performs Bayesian model-averaging[22]. Indeed, renamed blending, stacking was extensively used in the two top performers in the recent Netflix competition[23].

References

- ^ Opitz, D.; Maclin, R. (1999). "Popular ensemble methods: An empirical study". Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 11: 169–198. doi:10.1613/jair.614.

- ^ Polikar, R. (2006). "Ensemble based systems in decision making". IEEE Circuits and Systems Magazine 6 (3): 21–45. doi:10.1109/MCAS.2006.1688199.

- ^ a b Rokach, L. (2010). "Ensemble-based classifiers". Artificial Intelligence Review 33 (1-2): 1–39. doi:10.1007/s10462-009-9124-7.

- ^ Kuncheva, L. and Whitaker, C., Measures of diversity in classifier ensembles, Machine Learning, 51, pp. 181-207, 2003

- ^ Sollich, P. and Krogh, A., Learning with ensembles: How overfitting can be useful, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 8, pp. 190-196, 1996.

- ^ Brown, G. and Wyatt, J. and Harris, R. and Yao, X., Diversity creation methods: a survey and categorisation., Information Fusion, 6(1), pp.5-20, 2005.

- ^ Accuracy and Diversity in Ensembles of Text Categorisers. J. J. García Adeva, Ulises Cerviño, and R. Calvo, CLEI Journal, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 1 - 12, December 2005.

- ^ Ho, T., Random Decision Forests, Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, pp. 278-282, 1995.

- ^ Gashler, M. and Giraud-Carrier, C. and Martinez, T., Decision Tree Ensemble: Small Heterogeneous Is Better Than Large Homogeneous, The Seventh International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications, 2008, pp. 900-905., DOI 10.1109/ICMLA.2008.154

- ^ Tom M. Mitchell, Machine Learning, 1997, pp. 175

- ^ Breiman, L., Bagging Predictors, Machine Learning, 24(2), pp.123-140, 1996.

- ^ Hoeting, J. A.; Madigan, D.; Raftery, A. E.; Volinsky, C. T. (1999). "Bayesian Model Averaging: A Tutorial". Statistical Science 14 (4): 382–401. doi:10.2307/2676803. JSTOR 2676803.

- ^ David Haussler, Michael Kearns, and Robert E. Schapire. Bounds on the sample complexity of Bayesian learning using information theory and the VC dimension. Machine Learning, 14:83–113, 1994

- ^ Domingos, Pedro (2000). "Bayesian averaging of classifiers and the overfitting problem". Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). pp. 223–-230. http://www.cs.washington.edu/homes/pedrod/papers/mlc00b.pdf.

- ^ Monteith, Kristine; Carroll, James; Seppi, Kevin; Martinez, Tony. (2011). "Turning Bayesian Model Averaging into Bayesian Model Combination". Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks IJCNN'11. pp. 2657–2663. http://axon.cs.byu.edu/papers/Kristine.ijcnn2011.pdf.

- ^ Bernard Zenko, Is Combining Classifiers Better than Selecting the Best One, Machine Learning, 2004, pp. 255--273

- ^ Bensusan, Hilan and Giraud-Carrier, Christophe G., Discovering Task Neighbourhoods Through Landmark Learning Performances, PKDD '00: Proceedings of the 4th European Conference on Principles of Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, Springer-Verlag, 2000, pages 325--330

- ^ Wolpert, D., Stacked Generalization., Neural Networks, 5(2), pp. 241-259., 1992

- ^ Breiman, L., Stacked Regression, Machine Learning, 24, 1996

- ^ Smyth, P. and Wolpert, D. H., Linearly Combining Density Estimators via Stacking, Machine Learning Journal, 36, 59-83, 1999

- ^ Wolpert, D.H., and Macready, W.G., An Efficient Method to Estimate Bagging’s Generalization Error, Machine Learning Journal, 35, 41-55, 1999

- ^ Clarke, B., Bayes model averaging and stacking when model approximation error cannot be ignored, Journal of Machine Learning Research, pp 683-712, 2003

- ^ Sill, J. and Takacs, G. and Mackey L. and Lin D., Feature-Weighted Linear Stacking, 2009, arXiv:0911.0460

External links

- Ensemble learning at Scholarpedia, curated by Robi Polikar.